(The French airfield in Mavrovouni English text follows))

Σε απομνημονεύματα Γάλλων αξιωματικών και ημερολόγια στρατιωτών του Α’ Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου αναφέρεται συχνά η ύπαρξη ενός στρατιωτικού αεροδρομίου κοντά στη Σκύδρα (τότε Βερτεκόπ). Ο πατέρας μου, που ήταν 10 ετών το 1916, γνώριζε την ύπαρξη στρατιωτικού αεροδρομίου κάτω στον κάμπο της Έδεσσας, αλλά δεν ήξερε την ακριβή τοποθεσία. Του έκαναν, όμως, μεγάλη εντύπωση οι τεράστιοι αντιαεροπορικοί προβολείς που βρίσκονταν στη Σκύδρα. Όπως έλεγε χαρακτηριστικά, οι προβολείς ήταν τόσο δυνατοί που τον τύφλωναν όταν τα φώτα στρέφονταν προς την Έδεσσα μετατρέποντας τη νύχτα σε μέρα. Κάποιες έρευνες πέρυσι, ωστόσο, απέδωσαν καρπούς. Το αεροδρόμιο βρισκόταν ακριβώς πίσω από το λόφο του Μαυροβουνίου, όχι ορατό από την Έδεσσα, αλλά πολύ κοντά στο Βρετανικά Γενικά Νοσοκομεία 36 και 37 και σε απόσταση περίπου δύο χιλιομέτρων από τον Σιδηροδρομικό Σταθμό Σκύδρας.

Η τοποθεσία του αεροδρομίου όπως ήταν στον Α’ ΠΠ και όπως είναι σήμερα

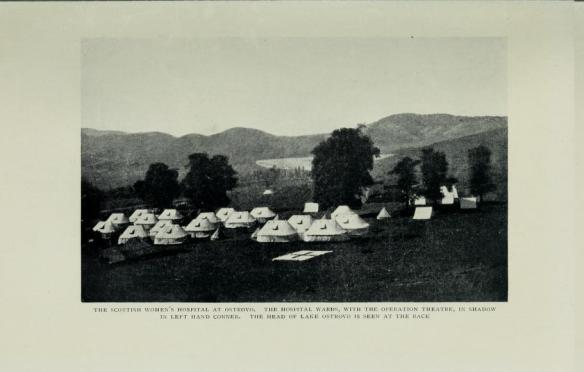

Με το γράμμα Α σημειώνεται η θέση του αεροδρομίου, Από την άλλη πλευρά του λόφου βρίσκονταν τα δυο βρετανικά νοσοκομεία 36 και 37.

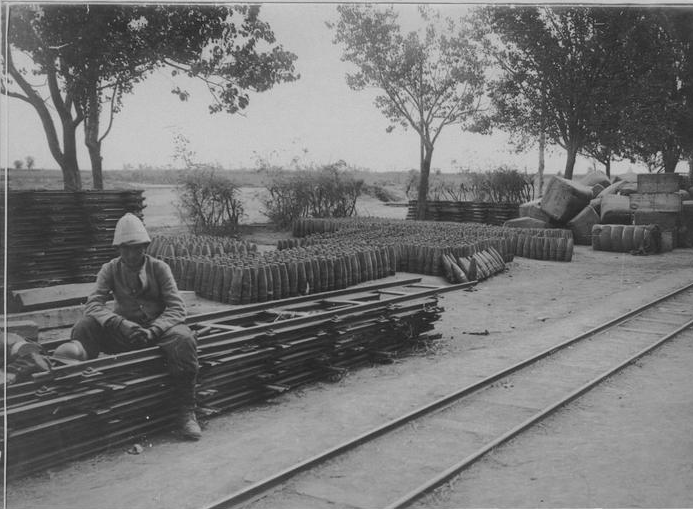

Η εναέρια φωτογραφία της εποχής δείχνει τα μεγάλα υπόστεγα του αεροδρομίου και τις σκηνές του προσωπικού. Στο βάθος μόλις διακρίνεται ο σιδηροδρομικός σταθμός της Σκύδρας ενώ η ευθεία οδός που χάνεται στην κάτω δεξιά γωνία της φωτογραφίας είναι η γραμμή του τρένου ντεκοβίλ προς Αριδαία. Πίσω από τον λόφο βρίσκονταν τα δυο βρετανικά νοσοκομεία.

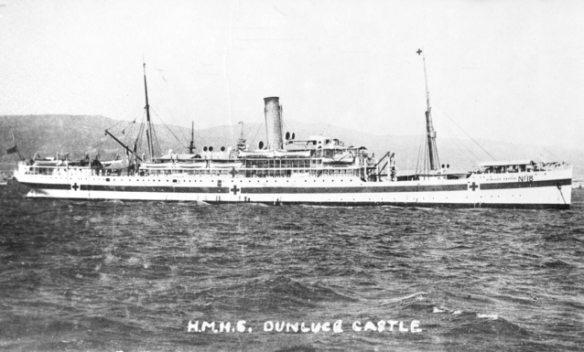

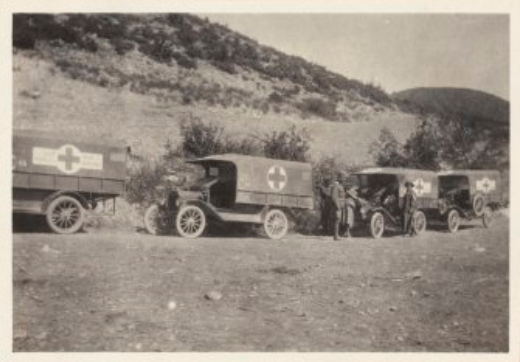

Στο αεροδρόμιο είχε τη βάση της η γαλλική μοίρα N387 (escadrille N387). Η Μοίρα N387 δημιουργήθηκε στα τέλη του 1915, αρχικά ως N87, πριν ενταχθεί στον Γαλλικό Στρατό της Ανατολής στη Θεσσαλονίκη (Armée Française d’Orient-AFO) υπό τον στρατηγό Μορίς Σαράιγ (Maurice Sarrail). Έφτασε στη Θεσσαλονίκη στις 20 Νοεμβρίου 1915 με το καταδρομικό «Σινά» και τοποθετήθηκε αρχικά στο αεροδρόμιο Θέρμης (Σέδες). Τον Ιούνιο του 1916 τέθηκε με άλλες τέσσερις μοίρες στη διάθεση του Σερβικού Στρατού ενσωματώνοντας ταυτόχρονα Σέρβους πιλότους και μηχανικούς. Όλες οι μοίρες που βοηθούσαν τον σερβικό στρατό έλαβαν τον πρόσθετο αριθμό 3 για να διακριθούν από τις άλλες γαλλικές μοίρες, έτσι το Ν87 έγινε Ν387. Αυτές οι μονάδες σχημάτισαν ένα αυτόνομο τμήμα αεροπορίας υπό τον Γάλλο διοικητή Ροζέ Βιτρά (Roger Vitrat). Στις 2 Αυγούστου 1916 η μοίρα N387 εγκαταστάθηκε σε αεροδρόμιο κοντά στη Σκύδρα, κεντρική θέση ανεφοδιασμού του σερβικού στρατού που είχε τοποθετηθεί καθόλο το μήκος της οροσειράς του Βόρα.

Τα αεροπλάνα παραρατεταγμένα στο αεροδρόμιο.

Επίσκεψη του πρίγκηπα Αλεξάνδρου της Σερβίας στο αεροδρόμιο

Παρασημοφόρηση από τον διοικητή Ντενέν

Τα χτυπημένα αεροπλάνα γίνονταν πηγή εξαρτημάτων

Υπό τον διοικητή Βιτρά η εκπαίδευση των Σέρβων πιλότων και μηχανικών στη γαλλική μοίρα ήταν πολύ επιτυχημένη. Σήμερα θεωρείται ότι η μοίρα αυτή αποτέλεσε την βάση για τη δημιουργία της σερβικής πολεμικής αεροπορίας. Ωστόσο, η σχετική αυτονόμηση που επέβαλε ο Βιτρά σε σχέση με την υπόλοιπη γαλλική αεροπορία υπό τον διοικητή Βίκτορα Ντενέν (Victor Denain) δημιούργησε έντονες τριβές τόσο με τον Ντενέν όσο και με τον Σαράιγ. Τον Ιούνιο του 1917 ο Vitrat έδωσε νέα ονόματα στις μονάδες του. Το N387 έγινε N523. Ο στρατηγός Σαράιγ θεωρώντας ότι οι απόψεις του Βιτρά ήταν υπερβολικά φιλοσερβικές, κατάφερε τελικά να τον στείλει πίσω στη Γαλλία τον Σεπτέμβριο του 1917, προς μεγάλη απογοήτευση της σερβικής ανώτατης διοίκησης. Μετά την αναχώρηση του Βιτρά, ο διοικητής Ντενέν αναδιοργάνωσε ολόκληρη την αεροπορία υπό την διοίκηση του (Σερβικές, Γαλλικές και Βρετανικές μοίρες). Οι σχέσεις όμως του στρατηγού Σαράιγ με την σερβική διοίκηση είχαν χειροτερέψει τόσο που ήταν δύσκολο να παραμείνει ως αρχηγός των συμμαχικών δυνάμεων του Μακεδονικού Μετώπου. Έτσι αντικαταστάθηκε στις 22 Δεκεμβρίου του 1917 από τον στρατηγό Γκιγιομά (Adolphe Guillaumat).

The French airfield in Mavrovouni

In memoirs of French officers and diaries of soldiers there was often mention of a military airport close to Skydra (Σκύδρα then Vertekop). My father, who was 10 years old in 1916, was aware of the existence of a military airfield down in the plain of Edessa, but could not tell the exact location. He was, however, greatly impressed as a young child by the huge anti-aircraft searchlights located in Skydra (then Vertekop) which blinded him when the lights were directed towards Edessa (then Vodena) turning night into day. Some research last year, however, bore fruit. The airport was, in fact, located just behind the hill of Mavrovouni village, not visible from Edessa, but very close to 36 and 37 British General Hospitals at a distance of about a mile from the Skydra RR Station.

By comparing the landscape of an old and a new photo it was easy to deduce the location of the airfield

With letter A the “Vertekop” airfield. West of Mavrovouni hill were located the 37 and 36 British general hospitals

An aerial photo of the airfield showing the east side of the Mavrovouni hill. On the west side of the hill were located the 36 and 37 hospitals. In the background one can hardly distinguish Skydra (then Vertekop) village and in straight line the road and railway from Skydra to Edessa. Next to the railway we can perceive the depot of the 2nd Serbian Army. On the right lower corner of the photo we can see the Decauville railway line and the road lead to Almopia and the Voras (Moglena) mountain range

The airfield was the base of French squadron N387 (escadrille N387). Squadron N387 was created at the end of 1915, originally as N87, before joining the French Army in Thessaloniki under General Maurice Sarrail (Armée Française d’Orient-AFO). It arrived at Thessaloniki on November 20, 1915 with the cruiser “Sinai” and was fixed initially at Thermi (Θέρμη then Sedes) airfield. In June 1916 it was placed with four other squadrons at the disposal of the Serbian Army integrating at the same time Serbian pilots and engineers. All squadrons with the Serbian Army received the additional number 3 to be distinguished from the other French squadrons, so N87 became N387. These units formed an autonomous aviation section under the French commander Roger Vitrat, a veteran pilot with the Serbs in autumn 1915 and the Great Retreat. On 2 August 1916 squadron N387 was established in an airfield near Skydra (then Vertekop) village, a central position for the Serbian army, where it stayed most of the time up to the end of the war.

Airplane graveyard – the source of spare parts for repairs

Prince Alexander of Serbia in a visit

The planes in stand-by

Commander Denain decorating pilots

Under commander Vitrat the integration of Serbian pilots and engineers into the French squadron was very successful. However, the lack of clear directives concerning the relations of his autonomous section and the rest of the French aviation under commander Victor Denain created strong frictions between Vitrat on one hand and Denain and Sarrail on the other. In June 1917 Vitrat gave new names in his squadrons. N387 became N523. General Sarrail, considering that Vitrat’s views were too pro-Serb, succeeded eventually in sending him back to France in September 1917 to the big consternation of the Serbian high command. Following Vitrat’s departure, Commander Denain reorganized the whole aviation of the Armée d’Orient under his supervision (Serbian, French and British – the Royal Flying Corps). One can say, however, that the five Vitrat’s squadrons of the Salonika capmaign formed the core of the future Serbian aviation.